In Atlanta, an area known as Five Points was originally a boundary point between Creek and Cherokee lands where their trails converged. In 1845, after the coming of white settlers, this site became the location of Atlanta’s first general store. Over the next century, the Five Points area began to build an identity as the heart of the city (until the 1960s when there was the flight of white citizens and urban activities to the suburbs). Along the way, however, there was the American Civil War, and the City of Atlanta was devastated by the invasion of Union troops in July of 1864. With intense strategic planning and implementation in the aftermath of destruction and the ending of the War, enterprising stakeholders quickly rebuilt the City. By the turn of the twentieth century, Atlanta was again steadily on the rise weathering the storms of a growing nation, including the Great Depression (1929-1939). In 1934, in the midst of the Great Depression, Five Points as Atlanta’s City Center was still enjoying its heyday and stood witness to a relatively modest event. Charlie Herren, a former prizefighter opened a small restaurant, which he named after himself – Herren’s. By 1939, the restaurant had moved to another location quite close by, 84 Luckie Street, a site where under new ownership and management, Herren’s began to make its mark as the first fine dining establishment in Downtown Atlanta for the “general public.”

To be noted, in 1939 creating an option for fine dining for the general public was an innovative change in Atlanta food services. It meant that diners who were not members of private clubs but wanted a nice option for downtown dining had one. During this era, however, there was a caveat. In keeping with the expectations and practices of the racially segregated South, such places were designed for and open to “whites only” and were just not conceivable as options available for African Americans. But, times were changing, and Herren’s would find its way, not only into the history of food services in Atlanta, but also into the story of a changing city and nation. This point suggests that Herren’s, like so many of the spaces in which we live our lives, has been more than simply a geographical site. It has functioned instead as a community “memory bead,” capable of bearing witness from generation to generation to the lives and histories of our comings and goings—if, in fact, we are committed to keeping those memories and the stories associated with them alive and a meaningful part of our city’s lore.

Luckie Street

Luckie Street, as the site of Herren’s Restaurant for over three decades, is itself a part of the richly woven fabric of this story, and it is interesting to ponder the linkages for how it came to be so. In 1837, Atlanta was established explicitly as the terminus point of the Atlantic & Pacific railway line. Just nineteen years later, by 1856, it was developing steadily and rapidly as a place where business happens and developing a reputation as the “Gate City of the South.” It was a nexus for innovation in business, manufacturing, transportation, agriculture, medicine, and technology. One of these businesses was the Atlanta Gas Light Company (AGL), which rose innovatively in 1855 to the opportunity to light the city’s streets, thereby increasing with technological solutions personal safety and convenience as well as economic development and sustainability. Led by William Helme of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, AGL developed the infrastructure to create this much needed resource, installing 50 gas lamps across the city. One of the lamps was erected on the corner of Peachtree Street at Alabama Street (now located in Underground Atlanta at the Five Points Marta Station). As circumstances would have it, in 1864 Union General William Tecumseh Sherman determined that dealing Atlanta an indisputable blow and blazing a dramatic trail with his troops from Atlanta across Georgia to the sea was the way to end the American Civil War. The very spot of the lamp post on Peachtree Street at Alabama Street in Five Points became part of ground zero for the Battle of Atlanta.

The invasion began with a barrage of artillery shells. With this very first battery, Solomon (Sam) Luckie was hit, among the first civilians to be injured in the battle. Luckie, one of 40 free African Americans living in Atlanta before the Civil War (1860-1865), was the owner and operator of the bath and barber salon in the nearby Atlanta Hotel, which was destroyed in the barrage. On this fateful day, Luckie was standing under the gas lamp at Peachtree and Alabama Street talking casually with a few others when he was wounded. Having survived the blast, Luckie was taken by the men with whom he had been talking to a nearby physician, but he soon died. In 1893, a portion of the street, including the gas lamp, was renamed Auburn Avenue, with the section of this street beyond Peachtree Street, being subsequently named Luckie Street in Solomon Luckie’s honor. The story of this incident is memorialized by a historical marker at the gas lamp in Underground Atlanta where it occurred.

Herren’s Restaurant for Fine Dining

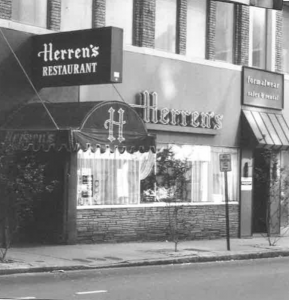

In 1934 in the middle of the Great Depression and with the rise of Benito Mussolini in Italy and Adolph Hitler in Germany as precursors of World War II, Herren’s Restaurant opened in downtown Atlanta in a small space near Five Points, named after its owner, Charles “Red” Herren, a prize fighter. Shortly thereafter, he moved the restaurant to 84 Luckie Street, where in 1939, he sold the restaurant to Guido Negri, an Italian immigrant who was an experienced, highly respected restaurant manager in the City of Atlanta. Under Negri’s control, Herren’s became the first restaurant for fine dining in downtown Atlanta open to the general public. The Negri family (including Negri’s wife and children) owned and operated the restaurant for the next forty years, as it evolved into the storied restaurant that many still remember today, frequented by the Atlanta elite and a broad range of prestigious visitors to the city. After Guido died suddenly in August 1942, Herren’s was operated by his wife Amalia who in 1947 convinced her son Edward to take over operations.

Under Ed Negri’s leadership, Herren’s thrived with Negri recognized locally and nationally as a leader in the food industry and the restaurant business, and as an active supporter of various causes in the city. In fact, with its convenient location on Luckie Street, in the heart of the city during that time period, so close to Peachtree Street, Forsyth Street, and Five Points, Herren’s gained an iconic status as the place to go in Atlanta for lunch for both downtown businessmen and downtown shoppers, and it became noted at both lunch and dinner for several of its iconic offerings, including steaks, live lobsters, and two quite specific desserts: freshly made cinnamon rolls and ice box lemon pie.

A Transformative Moment

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Herren’s became known for something of quite a different order. On June 25, 1963, it took a place of distinction as the first white-owned restaurant in Atlanta to open its doors voluntarily to African American customers. As Civil Rights activism heated up in the City of Atlanta, Ed Negri was an active member of the business leaders of the community, a group that included both white members (e.g., Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., 1962-1970) and African American (e.g., Jessie Hill, Jr., civil rights leader and CEO of the Atlanta Life Insurance Company). This bi-racial group was meeting regularly to strategize about how to keep Atlanta from becoming another fiery place like Birmingham, Alabama, with the violence that was occurring there and elsewhere across the South. Their solution was to provide a different leadership in “the City too busy to hate,” a tag line coined in the 1940s during the administration of Mayor William Berry Hartsfield (1937-1941; 1942-1961) who set the pace in Atlanta for fiscal restraint and bi-racial coalition.

Despite resistance from the Ku Klux Klan and from segregationists, such as Lester Garfield Maddox (owner of Pickrick Cafeteria and future governor of the State of Georgia, 1967-1971), the bi-racial coalition determined that Atlanta needed to desegregate voluntarily, with all restaurants leading the way by desegregating on the same day. Negri, however, was the only one who actually followed through on the date designated. He invited Dr. Lee R. Shelton (an African American physician, a renowned general surgeon in the city, a political activist, and a member of the bi-racial planning group), his wife Delores, and her mother Alberta Walker to dine at Herren’s. They came to the restaurant and dined without incident—even though the event itself drew heated national and international attention to Negri as the business owner who permitted this dramatic social change. Ultimately, however, other restaurants and businesses in Atlanta, with some exceptions, followed suit even before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened the floodgates of social change.

In Atlanta, the move toward social justice did indeed continue: with a coalition of leadership from the white community and the African American community; with the enthusiastic activism of the Atlanta Student Movement, led by student leaders from the Atlanta University Center, including among others: Roslyn Pope, Lonnie King, Julian Bond, Herschelle Sullivan, Carolyn Long, James Felder, Marion Bennett, and Mary Ann Smith; with the activism of a coalition of protestant ministers, and more. In other words, many stakeholders from across the Atlanta community and across generations came together during the 1960s to continue what time has confirmed as an ever-present struggle for social justice in the United States. Atlanta burned in the 1860s. It did not burn again in the 1960s.

A New Life for Herren’s

Herren’s continued to operate in Atlanta until the character of downtown Atlanta shifted, with the flight of businesses and white residents to the suburbs, and with the coming of MARTA (the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority) which facilitated the shift of downtown shopping to the suburbs as well. Herren’s closed its doors on November 13, 1987, and was boarded up until 2002 when Bill Balzer (an executive with United Parcel Service) and his wife Peg, award-winning patrons of the arts in Atlanta, purchased the site and donated it to Theatrical Outfit, the second oldest professional theatrical company in the city. At the time, Bill Balzer was chair of the Theatrical Outfit Board, and he and Peg Balzer became the lead patrons in creating a state of the arts performance space for what is now the Balzer Theater at Herren’s.

The Balzer Theatre is a 200-seat theatre with practice spaces, offices areas, and areas to support operational needs for Theatrical Outfit. The total renovation of the space received LEED status and in 2017 is part of a revitalization of downtown and midtown Atlanta areas. Founded in 1976, Theatrical Outfit has operated under the guidance and leadership of Tom Key who has served as Artistic Director since 1995. As stated on the Theatrical Outfit website, Key is “dedicated to the theatrical art form as a catalyst to creating community” where the mission of the company is to “tell ‘Stories that Stir the Soul.” He is a renowned actor himself who has appeared in well over 100 productions across the country and is one of Atlanta’s most celebrated and award-winning performing artists. In keeping with the spirit of Herren’s over the decades, Theatrical Outfit continues the spirit of the space as a community-centered and socially conscious site where Atlantans and visitors to the city from across communities, belief systems, and interests can gather, be entertained, and engage in important conversations together.

Accomplishments of Key Players

Charlie “Red” Herren (1884 – 1953)

In the early part of the twentieth century, Charles Dewitt “Red” Herren was a prizefighter. In 1934, he decided to go into the restaurant business, opening a small restaurant in Five Points, which he moved to 84 Luckie Street shortly thereafter. In 1939, he sold the restaurant to Guido Negri and spent most of his time on his farm, Herren’s Evergreen Farm located on Peachtree Street at Third Street. The farm was not successful, and he opened another restaurant, also named Herren’s, down the street from the Negri enterprise. It too was not successful. Herren and his wife Anna Ceclia Herren (1899 – 1975) moved to Florida where he owned and managed an apartment building. Herren died in 1953.

Guido Negri (1886 – 1942)

Born in Trento, Italy, Guido Negri left his home country at fourteen to join his brother Mario in London. His brother was working at a large hotel and helped him to get a job there as a bootblack, the beginning of what would become a remarkable career. By the beginning of World War I, he was working for the Hamburg-American Steamship Line and married to Amalia Negri (1891 – 1967) from Molare, Italy, where their first child was born. As the war escalated, he moved his family to New York where Guido left the Steamship Line to work for the New York Biltmore Hotel and where he and Amailia became the parents of three more children. As the war was drawing to a close, the Biltmore assigned Guido to the U.S. Navy at their request to take care of accommodations and food preparations for President Woodrow Wilson’s party as they traveled to peace conferences in Europe.

After the war, in 1924, the Biltmore re-assigned Guido once more, and he moved his family (Amalia and four children) to Atlanta. His job was to oversee the design of the food and beverage facilities at the new Biltmore Hotel in Atlanta and ultimately to manage them. Shortly after the new hotel opened, he was hired away by the prestigious Piedmont Driving Club, where he remained until anti-Italian sentiments at the Club led to his being fired. He was hired by Carling Dinkler, owner of Atlanta’s Ansley Hotel (later the Dinkler Plaza) to study food service operations at St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans (part of the Dinkler Hotel chain) and the operations of other prestigious restaurants in the area. Leaving his family in Atlanta, Guido was by that point among the most experienced restauranteurs in the South. When the opportunity for him to own his own restaurant occurred, he enthusiastically pursued it. He moved back to Atlanta and his family, and arranged to purchase Herren’s in 1939.

During this time period, as Guido was developing his expertise and gaining an incredibly rich set of experiences in the restaurant business, he was also active in the community. He was a leader in the small Italian immigrant community in Atlanta, serving, for example, as Honorary Representative of the Italian Government in Atlanta. He was an avid supporter of the community’s music and the arts scene, working, for example, with financier Victor Kriegshaber to establish the Atlanta Philharmonic Orchestra, and he was also a talented musician himself, who received favorable response as a composer and singer. After 1939, he was also transforming Herren’s into the finest restaurant in Atlanta.

In 1942, however, Guido died very suddenly. His wife Amalia was pushed into the lead for the business. With the help of family and friends, she stepped in to oversee the management and operation of Herren’s through World War II, until 1947 when she convinced her son Edward to take over. Even after Ed took the helm, Amalia continued to help out, remaining active until the day of her death in 1967.

Edward John Negri (1921 – 2013)

Born in New York, Edward Negri grew up in Atlanta, attending Sacred Heart Elementary School, O’Keefe Junior High School, the Atlanta Boys’ High School, and the Georgia Institute of Technology, where he entered in the fall of 1940. After the United States entered World War II in 1941, Ed interrupted his studies to start training as a pre-flight aviation cadet in the U.S. Army Air Corps, serving ultimately as a flight instructor. During this period, Ed married his high school sweetheart, Jane Fuller Negri (1924 – 2009); he returned to Georgia Tech to graduate in mechanical engineering; for a short while he worked with Delta Heating and Air Conditioning — before his mother, Amalia Negri, convinced him to take over the family’s restaurant; over the next few years Ed and Jane became parents to three children; and for the next four decades Ed became a very successful restauranteur and a leading citizen in the Atlanta community. Among his long list of accomplishments, he was:

- An innovator in the restaurant business, with Herren’s being, for example, the first restaurant in Atlanta to install air conditioning. President of the Atlanta Restaurant Association.

- A director of the National Restaurant Association.

- A key figure in the “Save the Fox Theatre” campaign to preserve the iconic Fox Theatre, which was being threatened with destruction.

- A leader in raising funds to renovate Wren’s Nest, the home of Joel Chandler Harris, author of the Uncle Remus tales.

- A member of the boards of the Red Cross, Boy Scouts, Camp Fire Girls, United Appeal, and more.

- A leader in the creation of the Boy’s High Alumni Group and its first President.

- The owner and operator of the first downtown restaurant in the City of Atlanta to desegregate voluntarily on June 25, 1963.

After Herren’s closed its doors on November 13, 1987. Ed opened other restaurants — one in Buckhead, the new business area in North Atlanta, and a subsequent one in Cobb County. Neither venue garnered anywhere near the success of Herren’s, and the Negris retired.

Lee R. Shelton, MD

When Ed Negri agreed to desegregate Herren’s, he extended an invitation to dine to Dr. Lee R. Shelton, his wife Delores, and his wife’s mother Mrs. Alberta Walker. Negri had met Dr. Shelton at the meetings that were occurring among business leaders to negotiate the racial change that was happening across the South in support of finding non-violent paths to social justice and political and economic empowerment.

Dr. Shelton received his medical degree from Howard University in 1955, interned at the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C; completed a residency at the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital in 1959 and another at the Hughes Spalding Pavilion in Atlanta in 1961. By 1963, he was a general surgeon who was highly respected in the African American community; very much engaged with African American medical professional organizational activities; and actively engaged with Civil Rights activities and protests in Atlanta. Dr. Shelton provided medical services to the Atlanta community for over six decades.

When the Sheltons and Mrs. Walker entered Herren’s on June 25, 1963, they were well dressed and graciously composed outwardly, and they were quite apparently well-prepared inwardly for this key moment in the transformation of Atlanta. As the first to integrate a white restaurant for fine dining, they did what had to be done with courage. They enjoyed their meal without incident—as two worlds, previously segregated, intersected in downtown Atlanta as if doing so were “normal” even in the South.

Bill and Peg Balzer

By 2002, the building that had been the home of Herren’s Restaurant had seen far better days and had been boarded up for many, many years. Bill Balzer, a retired executive of the United Parcel Service, Inc., and Peg Balzer, a longstanding community volunteer, saw possibilities, however. Both are passionate advocates for the arts in the City of Atlanta, and especially the theatre. They purchased the building as lead donors (and board members) of Theatrical Outfit and donated it to the company. Their gift leveraged the fundraising for a $5 million renovation. The building was named in honor of the Balzers and is now known as The Balzer Theatre at Herren’s. The renovation receiving a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Silver Award, making it the first theatre in the country to receive this status as a green building. In 2011, the Balzers received the Turner Broadcasting Downtown Community Leadership Award.

Tom Key

A nationally successful actor, director, and playwright, Tom Key has brought his visionary and enthusiastic leadership to Theatrical Outfit. The company was established in 1976 in the Virginia Highland district of the city. Over the next decades, the group performed at several other locations as well, including the renovated Kress Five and Dime on Peachtree Street, the 14th Street Playhouse, and the Rialto Center for the Arts at Georgia State University. Artistic Directors have included David Head and Sharon Levy.

Since 1995 under Key’s leadership, Theatrical Outfit has maximized its longevity and success. With the Balzer Theatre, the company has now secured a new home in a space that seems thoroughly appropriate for performances designed to “stir the soul.” Setting a remarkable personal pace, Key has been a critical element as he and colleagues have continued to blaze distinctive artistic trails with conversations that matter to the community. He has himself set watermarks as one of the city’s most celebrated performing artists, as indicated by two examples from among the many awards that he has received in recognition of this work. He was presented the Governor’s Award in the Humanities and the Georgia Arts and Entertainment Legacy Award.

One important result to note: In a building that housed for almost 50 years a world class restaurant, we now have in the very same space a world class theatre company that is carrying forward a sustaining legacy.

Living Legacies

If it is possible for the spirit of a place to live on and leave remnants and resonances for subsequent generations, then such is the case of Herren’s, which was endowed with the spirit and commitments of Guido and Ed Negri (along with their spouses Amalia and Jane, who worked side by side with them; other members of the Negri family who grew up in the restaurant and worked there; all of the loyal employees who worked there over its 50 years; and generations of customers who enjoyed the cuisine). In this place of business, work, and culinary delight there existed community and connection, and the next generation of occupants is adding to these values. Tom Key and the Theatrical Outfit executives and employees; the actors and discussion leaders who participate in the events; and audiences from across the city and around the world all gather now continuing to create community and connection. This generation is adding value to the mix, including a commitment to environmental consciousness, an ongoing sense of socio-political responsibility through story and performance, and an ongoing commitment to nourish, not so much the body, but the soul through sight, sound, and robust conversation. One additional resonance, however, is that on opening nights in the lobby of the theatre, Theatrical Outfit has the habit of serving cinnamon rolls, made by the recipe made so famous by Ed Negri when the Balzer Theatre was indeed Herren’s Restaurant for fine dining—a tribute to the past and a very nice touch point for the present.

Selected References

- Allen, Ivan Jr. and Hemphill, Paul. Mayor: Notes on the Sixties. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971.

- “Atlanta.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/atlanta/antebellum.htm. 1 April 2017.

- “Atlanta.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/ 1 April 2017.

- Herren’s: A Sweet Southern Spirit. Director: Allen Facemire. Atlanta, GA: Salt Run Production, Inc. 24 February 2006. 27 minutes.

- Lefever, Harry G. Undaunted by the Fight: Spelman College and the Civil Rights Movement, 1957-1967. Macon: Mercer University P, 2005.

- Negri, Ed (with Michael J. Cain). Herren’s: An Atlanta Landmark, Past, Present, and Future. Roswell, GA: Roswell Publishing Company, 2005.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. The Civil War Era and Reconstruction: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- “Theatrical Outfit.” http://www.theatricaloutfit.org/. 15 April 2017.

- Poole, Sheila. “50 years ago, Herren’s opened door to family and integration.” http://www.myajc.com/events/years-ago-herren-opened-door-family-and-integration/I2qoLD6OAin6y9ZGy0SetI/ . 21 June 2013.

- “William B. Hartsfield.” http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/william-b-hartsfield-1890-1971. 15 April 2017.

Credits

- Page Author: Jacqueline Jones Royster, Dean, Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts

- Building Memories Project Team (Gene Kansas, Stephen Key, Steve Hodges)

- Partners: Bill and Peg Balzer; Theatrical Outfit

- Contributor and Advisor: Steve Negri; also see his fascinating account of Herren’s history at https://stevenegri.wordpress.com/2015/08/18/ye-olde-herrens-restaurant/