Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History

Note that this narrative was created in collaboration with the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Libraries as a Public Good

During the early years of Colonial America, books (which during this era needed to be imported from Europe) were very expensive and rare commodities. Facing this challenge, wealthy men often pooled resources to maximize their own access to materials by creating private book clubs. These membership organizations evolved into lending libraries that functioned by subscription, giving the membership group the privilege of freely borrowing from a range of materials that they would otherwise find difficulty to afford. Another advantage of club membership was that the clubs met regularly to engage in discussion and debate about issues related to religion and morality, education, politics, philosophy, art, and literature. These privileges were not generally available to non-elite groups, including middle and lower socio-economic classes, and the enslaved.

One of the first of these types of organizations in the American colonies was established in Philadelphia in 1727 by Benjamin Franklin and a group of his friends. The Junto (the meeting) was a mutual improvement group known also as the Leather Apron Club (made up mainly of tradesmen and artisans). This group gave rise to the establishment of the Library Company of Philadelphia on July 1, 1731. Franklin gathered 50 founding shareholders who pooled their resources, contributing 40 shillings and agreeing to pay 10 shillings per year, to purchase and build a library collection. After the Revolutionary War, the Library Company served as the Library of Congress while Philadelphia was the seat of national government. After more than 250 years, the Library Company’s collection has continued to grow and evolve. It serves now as an independent research library focused on American life and culture.

This example offers evidence of the commitment of public leaders, such as Benjamin Franklin, to the view that books, learning, and the creation of spaces for cultural and intellectual engagement are valuable for the community and indeed a public good. Franklin demonstrated his commitment to this view, however, in yet another way. In 1790, he donated a collection of books to a town in Massachusetts (that ultimately named their town after him). The residents of Franklin voted for the books “to be freely available for town members, creating the nation’s first public library” (“First Public Libraries”). With the rise of literacy in the newly formed United States of America, these types of free lending libraries became increasingly popular, and especially so after the American Civil War. To be noted, they did not follow a subscription model. Instead they were governed by boards, funded by taxes, did not charge for services, and were specifically focused on “serving the needs of the general public” (“First Public Libraries”). Along these lines, the first totally tax-supported library was established in Petersborough, New Hampshire, in 1833. The first large public library, containing over 16,000 volumes, was founded in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1848.

Surrounding this evolving American story of free and open access to library collections is quite inescapably the history of discriminatory practices across the nation and over almost the entire time of the nation’s existence. A striking example is the exclusionary racist practice in the South of the denial of access to public facilities and institutions to African Americans (which prevailed until the latter decades of the 20th century). Historically in the South, the notion of public became operationalized as having resources and assets that were funded by tax revenues but that were made available habitually for the privileged use of whites only. Even with the American Civil War occurring during the nineteenth century and the ending of chattel slavery, a “public, but not really open” framework ruled the day and actually became institutionalized in 1896 when the Supreme Court upheld the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson. This ruling created a separate-but-equal model that in both social and legal practice centralized the separateness of resources and assets but without critical attention to establishing and maintaining the material equality of them.

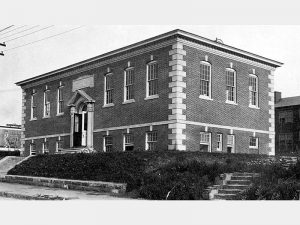

Free and Open Access Libraries in Atlanta

In Atlanta and the remainder of the South, African Americans could not use public libraries freely or openly. The first public library in the South for African Americans was indeed a separate one, established in 1905 in Louisville, Kentucky, with funding from Andrew Carnegie. Born in Scotland in 1835, Carnegie migrated with his family to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in 1848, where over the course of his life and work as an entrepreneur and business person, he accumulated considerable wealth and exercised a robust commitment to philanthropy. A specific focus of his philanthropy was education and, given his love of reading, also libraries. He funded more than 2800 libraries across the country. One of these libraries was the first public library in Atlanta, funded, as the Louisville library had been, in 1905. Access to the Atlanta Public Library, however, was not available to African Americans—even separate access—until an African American branch was opened at 333 Auburn Avenue on July 25, 1921. From that moment forward, the Auburn Avenue Branch started along its distinctive path as an invaluable anchor for culturally-informed public collections in the City of Atlanta. Over the decades, it has functioned as a repository for a full range of books and materials related to African American history and culture, and has now become a premier public research library, joining other research centers nationally in fulfilling critical roles as a cultural asset, not only for African Americans, but for the nation. These cultural assets were both public (those associated with publicly funded libraries) and private (those established as independent organizations or associated with historically African American colleges and universities).

A basic time line for the Auburn Avenue Library includes the following:

- The Auburn Avenue Branch of the Carnegie Library was established for African Americans on July 25, 1921.

- The director of the branch was Alice Dugged Cary (1921-1929).

- In 1934, the Negro History Collection of non-circulating books was established at the Auburn Avenue Branch.

- In 1936, Annie L. Watters McPheeters became the first African American professional librarian to be hired by the Atlanta Public Library. She was appointed Director of the Auburn Avenue Branch, serving from 1936-1949.

- In 1941, the University Homes Reading Room was established under the supervision of Director McPheeters, with Ethel Hawkins, an assistant librarian at Auburn Avenue and a resident of University Homes, volunteering to manage the room. In 1942, the Reading Room was designated the University Homes Branch and operated until 1962.

- In 1949, with the growing African American population in Westside communities, a third African American branch was established, the West Hunter Branch near the Atlanta University Center. Director McPheeters moved to be director the West Hunter Branch and took the Negro History Collection with her. She remained at the West Hunter Branch until 1966 when she left the Atlanta Public Library to take a position as reference librarian at Georgia State College (later Georgia State University). She was the first African American to hold this position, and she remained there until 1975.

- While she was at the West Hunter Branch, McPheeters was an advocate with several others for the desegregation of the Library , which happened in 1959. The Auburn Avenue Branch was closed to the public, and African Americans could enter the Central Library. However, the expectation was that they could read books in the basement of the building.

- In 1961, Irene Dobbs Jackson became the first African American to receive a library card from the Central Library, marking, for all practical purposes, the end of the segregated Atlanta Library System, a change that occurred as Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., who became known as a more forward thinking leader as a Southern mayor, took office.

- In 1970, the Negro History Collection was transferred from the West Hunter Branch to the Central Library as a special collection. Francine I. Henderson was appointed the first curator of the collection.

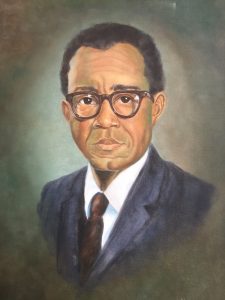

- On November 21, 1971, the Negro History Collection was renamed the Samuel W. Williams Collection on Black America in honor of Rev. Samuel W. Williams, former pastor of the Friendship Baptist Church and Professor of Religion and Theology at Morehouse College. N. Louise Willingham was named the curator of a newly established Special Collections Department.

- In 1993, the Atlanta-Fulton County Library System named the West Hunter Library in honor of Annie L. McPheeters, and at the Auburn Avenue Research Library, they named the main exhibition gallery after McPheeters and Alice Dugged Cary, educator and the first librarian of the Auburn Avenue Branch.

- In April 1994, the Samuel W. Williams Collection on Black America was transferred from the Central Library to the new Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History under the administrative leadership of Julie V. Hunter. On May 16, 1994, the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History opened to the public, becoming the first public research library of its kind in the Southeast.

- In 2008, the citizens of Fulton County voted in favor of a $275 million library bond referendum for capital improvements to the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System. In July 2014, the Auburn Avenue Research Library closed temporarily for renovation and expansion.

- The newly renovated and expanded Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History reopened on August 4, 2016, under the administrative leadership of Victor E. Simmons, Jr., following in this position: Julie V. Hunter, Joseph F. Jordan, and Francine I. Henderson.

Creating a Cutting Edge

As noted above, in 1921 the Auburn Avenue Branch Library became one of the first libraries in the country designated for African Americans. In 1994, the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History (AARL) became the first public research library on African American culture and history in the South. This distinction places AARL among the top research libraries in the United States with this mission, including in chronological order of origin:

- The Moorland-Spingarn Research Center was established within the holdings of Howard University, founded in 1867. The collection began with the donation of the private library of African American theologian Dr. Jesse E. Moorland in 1914. He was an alumnus and trustee of the university. This collection, which became known as the Moorland Foundation, was a catalyst for the university to centralize materials related to the Black experience. While several librarians were part of the development of the collection, in 1930 Dorothy B. Porter was appointed as the director. Under her guidance over the next 40 years, the collection expanded substantially and flourished. A key donation during this era came in 1946, when attorney and activist Arthur B. Springarn contributed his large collection of books and other materials. In 1973, the collection was re-organized as the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, named for these two original benefactors.

- The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library was established in 1925 as the Division of Negro History, Literature, and Prints, a special collection of the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library.The agreement for the New York Public Library was signed on May 23, 1895, to be anchored by collections from two former libraries that were not public libraries (Astor and Lenox) with funding from three foundations (Astor, Lenox, and Tilden). The signature facility to house the new combined collections was not completed until 16 years later with the building opening its doors on May 24, 1911. In the intervening years the library established the New York Free Circulating Library in February 1901, with Andrew Carnegie providing funding that same year to build a system of branch libraries in partnership with the city. The 135th Street Branch was opened in Harlem on January 14, 1905, and renamed in 1951 for African American poet and teacher Countee Cullen. In 1926, Puerto Rican-born scholar and bibliophile Arturo Alphonso Schomburg contributed his extensive personal library to the Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints, and served as the curator of the special collection from 1932 until his death in 1938. In 1940, the Division was renamed the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature, History and Prints. In 1972, the name was changed again, to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and designated a research library of the New York Public Library System.

- The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History of the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System was originally established in 1921 as the African American Branch at 333 Auburn Avenue. After several transitions, it officially re-opened its doors at 101 Auburn Avenue as a research library in April 1994. The Samuel W. Williams Collection on Black America (originally the Negro History Collection of non-circulating books) formed the foundation for the collection, along with various other collections, including, for example, a collection acquired through an adult education project jointly sponsored by the American Association of Adult Education, the American Library Association, and the Julius Rosenwald Fund.

- The Amistad Research Center was originally established in 1966 by the United Church Board for Homeland Ministries at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, to house the historical records of the American Missionary Association, an iconic abolitionist and interdenominational organization formed in 1846. In 1969, the Center became an independent non-profit organization and moved to Dillard University in New Orleans, finding ultimately a permanent home at Tulane University in 1987. With the American Missionary Association records forming the foundation for the Amistad Research Center, the collection expanded over the years to include a range of papers from individuals across many walks of life, focusing on the documentation and preservation of materials related to the history of the African Diaspora and civil rights.

From these beginnings, African Americans increasingly gained free and open access to books, information, and materials, and to public spaces that inspire and encourage intellectual engagement. In Atlanta, they were able to do so from 1921 through the Modern Civil Rights Movement in the Auburn Avenue Branch, the University Homes Branch, and the West Hunter Branch of the Atlanta Public Library. These pioneering public, but segregated, sites were an invaluable community resource that transitioned during during the heart of the Civil Rights Movement into the non-segregated sites of the Atlanta-Fulton County Library System. In the 21st Century, these resources now enable free and open access to all. Most distinctively, African American Librarians, who overwhelmingly were women, expanded, developed, and evolved the Negro History Collection of Non-Circulating Books over almost a century into the Auburn Avenue Research Library in African American Culture and History. AARL has become a dynamic space and infrastructure that preserves and protects books and other materials. It encourages the active participation of all stakeholders, regardless of personal identity, in documenting and celebrating the legacies and ongoing progress and prosperity of African Americans, not only in the City of Atlanta, but also the nation and the world. It functions as a site for the archiving, researching, and curating of African American history, life, and culture. It organizes and hosts a variety of programs, exhibitions, workshops, and more. In providing these services, AARL offers to the City of Atlanta and beyond a sustainable space within which to address and engage the changing needs of a vibrant cultural community within a diverse and complex urban environment. In doing so, AARL enacts in policy and practice the belief that these spaces are precious and vital spaces for the public good.

Key Players

The long line of people who have played important roles in the history and development of the Auburn Avenue Research Library begins with Alice Dugged Cary, the first educator and librarian to direct the Auburn Avenue Branch. The list of key players continues into the 21st Century.

Annie L. Watters McPheeters (1908 – 1994) was the first African American professional librarian in the Atlanta Public Library. Born in Floyd County, Georgia, McPheeters moved to Atlanta to attend Clark College, where she received a B.A. in English. After graduation she received a B.S. in library science and later an M.S. in library science from Columbia University in New York. McPheeters started her career as a teacher in the public schools of Georgia and South Carolina. In 1934, she was appointed in the Atlanta Public Library at the Auburn Avenue Branch as an assistant librarian and immediately began building the Negro History Collection. In 1936, she was appointed a full librarian, becoming the first professional African American librarian in the Atlanta Public Library System. In 1940, McPheeters married Alphonso McPheeters, an educator, with her leadership as a librarian continuing until her retirement in 1975. In addition to her distinctive professional accomplishments, McPheeters also published several books, including: Scarcity of Children’s Librarians in Public Libraries (1960) and a multivolume collection, Negro Progress in Atlanta, Georgia (1964 and 1972). She worked as a library acquisitions consultant for Pergamon Press. She was actively involved in several community organizations, including: Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, the Utopian Literary Club; and she remained a supporter of the Auburn Avenue Research Library throughout the remainder of her life. McPheeters’s story of dedication and excellence offers evidence of the larger story of African American women librarians who were trailblazers in creating, shaping, and advancing libraries in the African American community as a common public good. At AARL, the list includes:

- Alice Dugged Cary

- Mildred Gaines

- Anne Rucker Anderson

- Mae Z. Marshall Shepard

- Annie L. Watters McPheeters

- R. Leathers

- Goldie Culpepper Johnson

- Ethel Hawkins

- Francine I. Henderson

- N. Louise Willingham

- Janice White Sikes

- Julie V. Hunter

With this narrative, we celebrate them all and the longer list of all whom they inspired through their love of books, history, and culture.

Irene Dobbs Jackson (1908 – 1999) was born and raised in Atlanta in the Auburn Avenue neighborhood, the eldest daughter of highly respected Atlanta business and political leader John Wesley Dobbs. She was the first of the six Dobbs daughters to receive the B.A. degree from Spelman College. Graduating at the top of her class, she went on to receive an M.A. in French from the University of Grenoble (France). After returning to Atlanta, she married Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Sr., a graduate of Morehouse College who had also received training from the Garrett School of Divinity at Northwestern University. In 1933, he became the pastor of New Hope Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, where he was very active as well in politics and community action, and where he served as editor of a newspaper. In 1945, he brought his family back to Atlanta when he became the pastor of the iconic Friendship Baptist Church. During this time the Jacksons became the parents of six children, including their eldest son Maynard, Jr. who would later become the first African American mayor of the City of Atlanta. By 1956, Jackson was widowed and decided to return to France with her six children in tow to complete a PhD in French at the University of Toulouse (France). After completing the degree in 1958, Jackson returned to Atlanta and accepted a position at Spelman as Professor French and Chair of the Department. In 1959, she entered the Central Atlanta Public Library and became the first African American to receive a library card.

Samuel W. Williams (1912 – 1970) grew up in Chicot County, Arkansas. He received a B.A. in philosophy from Morehouse College and master of divinity degree from Howard University with further study from the University of Chicago. He was active in several civil rights organizations (e.g., the Southern Christian Leadership Council, where he was a founding member and vice president; the Community Relations Commission, where he was Vice Chair; the Atlanta Summit Leadership Conference, where he was a founder; and the Atlanta Branch of the NAACP, where he served as president). Williams joined the faculty of Morehouse College in 1946 as Chair of the Department of Philosophy and Religion, where he taught future leaders, such as: Samuel DuBois Cook, who would become President of Dillard University; Maynard H. Jackson, Jr., who would become the first African American mayor of the City of Atlanta; and Martin L. King, Jr, who would become the recognized leader of the Modern Civil Rights Movement. In 1947, he became assistant pastor of Friendship Baptist Church and pastor in 1954. After his death in 1970, the Atlanta Public Library renamed the Negro History Collection of Non-Circulating Books the Samuel W. Williams Collection on Black America on November 21, 1971.

Selected References

- Amistad Research Center. http://www.amistadresearchcenter.org/. 9 August 2017.

- “Andrew Carnegie.” https://www.biography.com/people/andrew-carnegie-9238756. 10 August 2017.

- “Annie L. McPheeters (1908 – 1994).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/education/annie-l-mcpheeters-1908-1994. 10 August 2017.

- At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: A Brief History of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Revised and Enlarged Edition. Philadelphia: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 2015.

- Auburn Avenue Research Library. http://www.afpls.org/aarl. 9 August 2017.

- “Benjamin Franklin’s Junto and Lending Library of Philadelphia.” http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/ideas/text4/juntolibrary.pdf 9 August 2017.

- “A Case Study: Atlanta.” A History of US Public Libraries. Digital Public Library of America. https://dp.la/exhibitions/exhibits/show/history-us-public-libraries/segregated-libraries/case-study-atlanta. 7 August 2017.

- “The Countee Cullen Library.” https://www.nypl.org/about/locations/countee-cullen. 10 August 2017.

- “First Public Libraries.” A History of US Public Libraries. Digital Public Library of America. https://dp.la/exhibitions/exhibits/show/history-us-public-libraries/beginnings/first-public-libraries. 7 August 2017.

- “History of the New York Public Library.” https://www.nypl.org/help/about-nypl/history. 10 August 2017.

- “Irene “Renie” Dobbs Jackson, 1908-1999.” http://sweetauburn.us/rendobbs.htm. 10 August 2017.

- “Jackson, Maynard Sr. (1898-1953).” http://www.blackpast.org/aaw/jackson-reverend-maynard-sr-1898-1953. 10 August 2017.

- The Library Company of Philadelphia. http://librarycompany.org/about-lcp/. 9 August 2017.

- Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. http://library.howard.edu/msrc. 9 August 2017.

- The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://www.nypl.org/about/locations/schomburg. 9 August 2017.

- The Spelman College Archives. http://www.spelman.edu/about-us/archives

- Wells, Rosa Marie. “Samuel Woodrow Williams, Catalyst for Black Atlantans, 1946-1970” (1975). ETD Collection for AUC Robert W. Woodruff Library. Paper 687.

Credits

- Page Author: Jacqueline Jones Royster, Dean, Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts

- Building Memories Project Team:

- Jacqueline Jones Royster, Executive Producer

- Steve Hodges, Project Manager

- Gene Kansas,Co-producer, Building Memories Podcast

- Stephen Key, Co-producer, Building Memories Podcast

- Partner: Auburn Avenue Research Library, http://www.afpls.org/aarl